Professor Lin Foxhall is Head of the University of Liverpool’s School of Histories, Languages and Cultures

The centuria was advancing on the Gaulish troops. ‘How motley and disorganised they look, thought Quintus scornfully, ‘no match for our well-disciplined force’, when as they drew closer the air was rent by the most raucous, ear-splitting noise he’d ever heard, drowning the shouts and songs of the raging warriors. Horses reared, men shrieked in terror and fled dropping their weapons, and in an instant, the well-oiled machine that had been his centuria collapsed into pandemonium. ‘Jove save us, this is worse than those damned elephants in Bruttium’, choked Quintus, as he struggled to maintain his footing in the chaos, ‘Can it be those trumpets? How on earth do they play them and what demons are pumping their lungs’.

This imaginary scenario is the kind of setting generally associated with the ‘carnyx’, a generic name assigned by modern scholars to the large, intimidatingly loud, trumpet-like instruments played by a number of the Iron-Age societies encountered by the Greeks and Romans. The term ‘carnyx’ appears only in a few obscure, late and unreliable ancient Greek texts. The most detailed ancient descriptions of the battles with these iron age groups (e.g. Polybius 2.29; Diodorus Siculus 5.30; Caesar, Gallic War 7.81, 8.20) never use the word ‘carnyx; instead they use the normal Greek or Latin words for ‘trumpet’ (salpinx and tuba).

We have only hostile witnesses to tell us what they sounded like, and since our ancient first-hand observers appear to have heard these instruments only in battle settings, we have no idea if, or how, they might have been played in other contexts.

At least as far as our sources were concerned, in war these instruments were deployed to make the loudest, scariest and most horrible noises possible. While there is perhaps some truth to this, it is equally possible that Greek and Roman ears were not attuned to the musical forms and traditions of their Iron Age contemporaries, and that what they perceived as noise would have been heard as inspiring music by more sophisticated indigenous listeners.If these instruments were played in other contexts, for example ceremonial, funereal or religious, perhaps they played different kinds of music, in contrast to a deliberate attempt to create as intimidating a soundscape as possible on the battlefield. We simply do not, and cannot, know this because there is no evidence one way or the other.

Visual depictions and actual finds of these trumpet-like instruments come from all over Europe. Generally they consist of a long tube, sometimes in sections, curved in various ways, or largely straight, and almost always with the bell in the form of a beautifully crafted animal head. Some have integral mouthpieces, but not all, and in the latter cases we cannot always be certain a separate mouthpiece was employed.

The range is diverse, and we cannot assume that they were all played or used in the same way. Nor should they necessarily be characterised as universally ‘Celtic’: Iron Age societies were highly localised and independent, even when they shared common traits, and the extent to which these instruments were meaningful as part of local identities as opposed to the wider group identities is debatable.

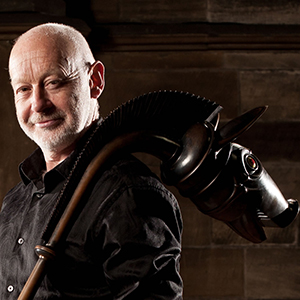

Musicians and instrument makers working with archaeologists have constructed working replicas to explore and recreate the possible sound worlds of these beautiful instruments. This has allowed composers and performers like John Kenny to probe the potential range of musical expression that could have been achieved by a skilled player. Sadly, we don’t know whether ancient musicians ever exploited the full range of this potential, or even how proficient the best were.

Kenny’s imaginative and sensitive use of extended brass technique has generated a fascinating modern repertoire to reinvent this instrument of the ancient past. And even if we never know what they actually played or even how their players conceptualized music, Kenny’s recreation can still movingly connect us to our European Iron Age predecessors and enable us to celebrate their cultures.

John Kenny will be playing the carnyx at the Victoria Gallery and Museum from 1pm on Wednesday March 9, as part of the University of Liverpool’s Lunchtime Concert series and Open Circuit Festival 2016