Thomas Harrison is the University of Liverpool’s Rathbone Professor of Ancient History and Classical Archaeology and chairs the Heritage, Arts and Culture Committee

“What are museums for? This – or more specifically, the purpose of one museum, the British Museum – was the question addressed in this year’s Postgate Lecture, by the British Museum’s Deputy Director, Jonathan Williams.

The answer – to cut an hour’s lecture to a few lines – was that it should return to something like its original eighteenth-century rationale. In the words of the 1753 Act of Parliament, the original British Museum’s collections should be for ‘public use to all posterity’, with ‘free access’ to ‘all studious and curious Persons’.

Urgent intellectual inquiry

It was never intended just as a repository of objects but as a site of urgent intellectual inquiry, where the world’s cultures could be placed in dialogue with one another, and inventions generated. Rather than just presenting the world’s cultures to its public in neatly packaged galleries, today’s British Museum then might likewise set comparable objects from different cultures alongside one another, to provoke new understanding.

As the British Museum initiates a public debate about the use of its collections, we should perhaps take a moment to reflect on the value of our own collections, within the University and the city at large.

When staff, students or public visitors discover the University’s collections – the Egyptian and Greco-Roman antiquities of the Garstang Museum, the fine art of the Victoria Gallery, or the departmental collections in dentistry, music, anatomy (to name just a sample of our collections within the University) – they invariably come away astonished. At the quality of our collections, certainly, but often also at the fact that they had never seen or heard of them before.

Great efforts have been made in the last decade. In particular, we have seen the creation of the Victoria Gallery & Museum as a hub, not only for our permanent collections but for a feast of temporary exhibitions (like the wonderful exhibitions on Edward Rushton and Dorothy Wordsworth open now). And yet in realising the potential of these collections, we have only scratched the surface.

Why should students come to our university rather than any other? For our degree programmes, of course, and hi-tech facilities. Our expert staff. Our shiny new halls of residence with their en-suite bathrooms. But also for the depth of the University’s history, its extraordinary collections, the magnificent buildings which survive across the campus, and for the broader cultural life (music, drama, film, dance…), both generated by our students and available on our doorstep.

It is not only a matter, however, of our ‘heritage assets’ being preserved, frozen in time, but of their being used – for teaching, for public engagement and for research. As Sir Hans Sloane wrote of the British Museum, so our collections too ‘should be ‘rendered as useful as possible’, both in ‘satisfying the desire of the curious’ and ‘for the improvement, knowledge and information of all persons’.

For a modern university, just as for the original British Museum, our collections (and our heritage more broadly) should be living: a stimulus to those that enjoy them, and continuously added to in reflection of our ongoing work. In the words of another prominent museum director, Tim Knox of Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum, we need to ‘make the place sing’.

Remarkable cultural renaissance

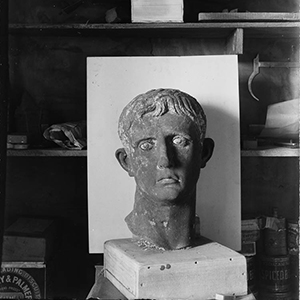

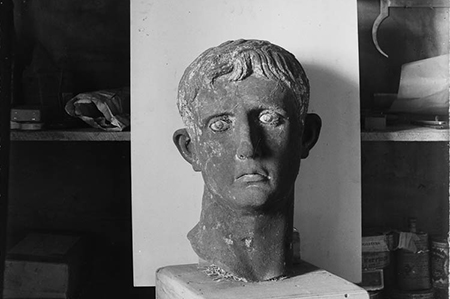

The city too has seen a remarkable cultural renaissance in the last decade, with a new Museum of Liverpool and high-profile events drawing millions to the city. But a bleak year of cuts in government funding has seen National Museums Liverpool, like other national museums, scaling back its activities, both in conservation and the development of its displays. The Classical collections will remain on temporary display, and the jewel in their crown, the magnificent Ince Blundell marbles – the best collection of Roman sculpture after the British Museum’s Townley collection – still cries out for the focus it deserves.

The challenges here are very substantial, but so is the potential prize. If crowds can flock in their tens of thousands to the British Museum to see the remains of Pompeii, then treasures such as the Ince Blundell marbles – gathered together by the great local collector, Henry Blundell, in the eighteenth century – can likewise be ‘rendered useful’ to a public, in Merseyide and internationally.

When we have learnt to recognise the value of this longer-term heritage – to celebrate the Blundell or Garstang collections, the built heritage of the campus and the city, as well as the Beatles and the Beat poets – only then perhaps will the city’s renaissance be complete.”